Shack Town

IOCO Memories

Chapter 2

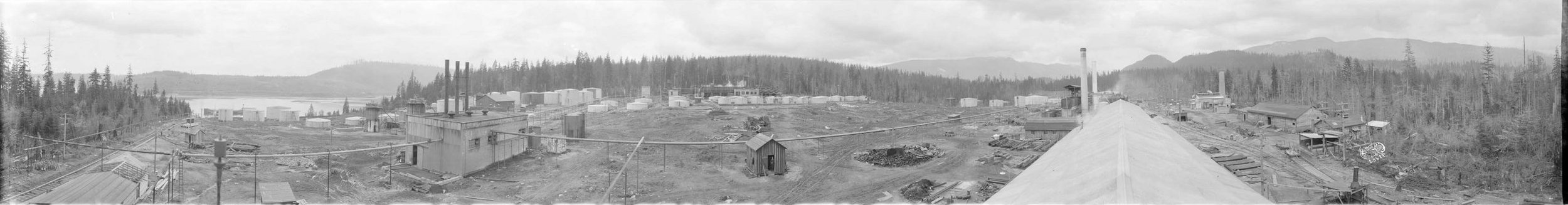

The company quickly built two large bunkhouses and a dining hall which fed 250 men for about 20 cents a meal. The Colony House boarded 50 men and 17 small cottages housed resident engineers and supervisors, mostly from Sarnia, Ontario. With just lanterns for lighting and wood stoves for heat, the conditions were harsh, especially for the eastern employees not used to primitive living.

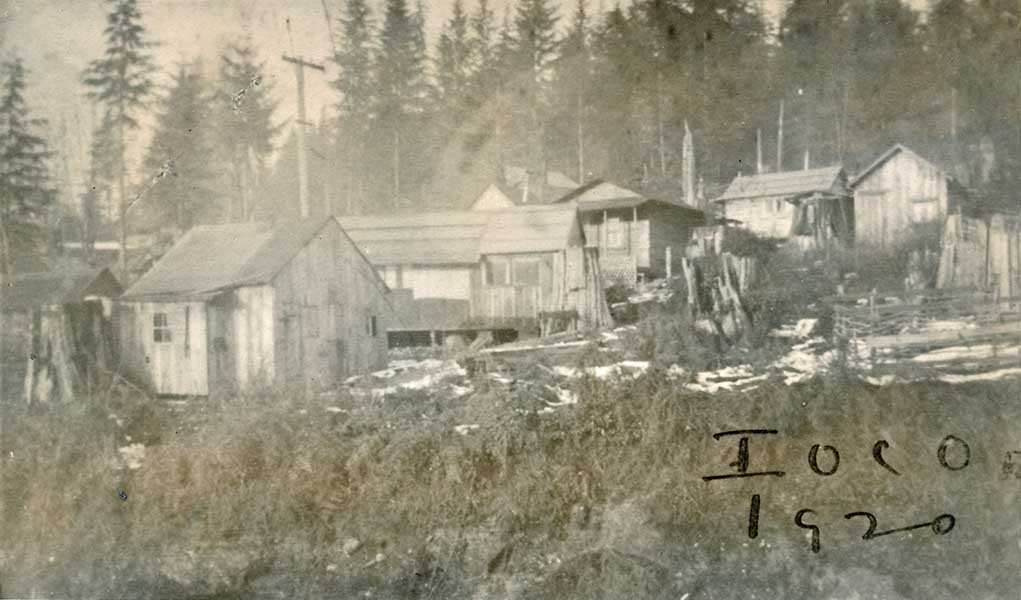

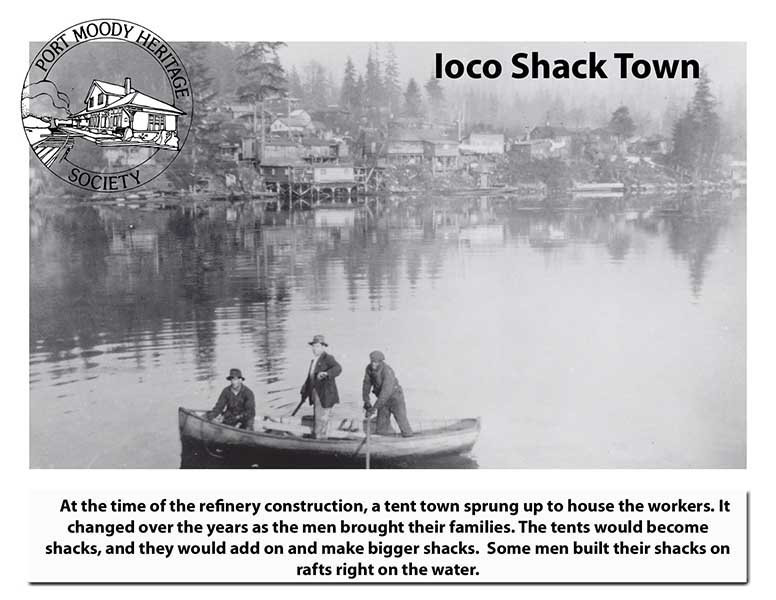

With the construction of the Imperial Oil refinery north east of Port Moody in 1914, workers from across the country flocked to the area. In the beginning, living quarters were limited and the company did what it could to accommodate its workers.

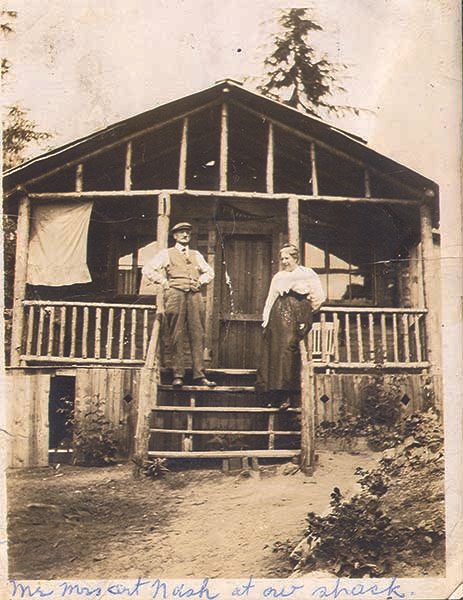

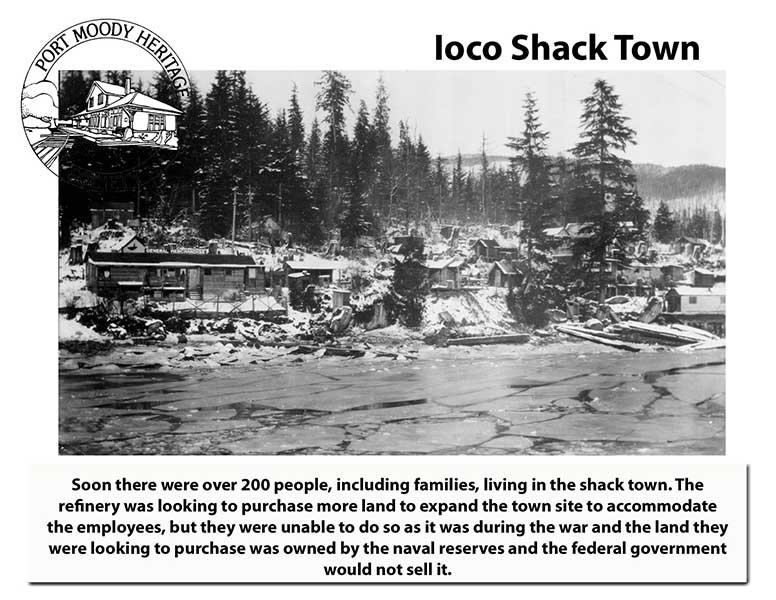

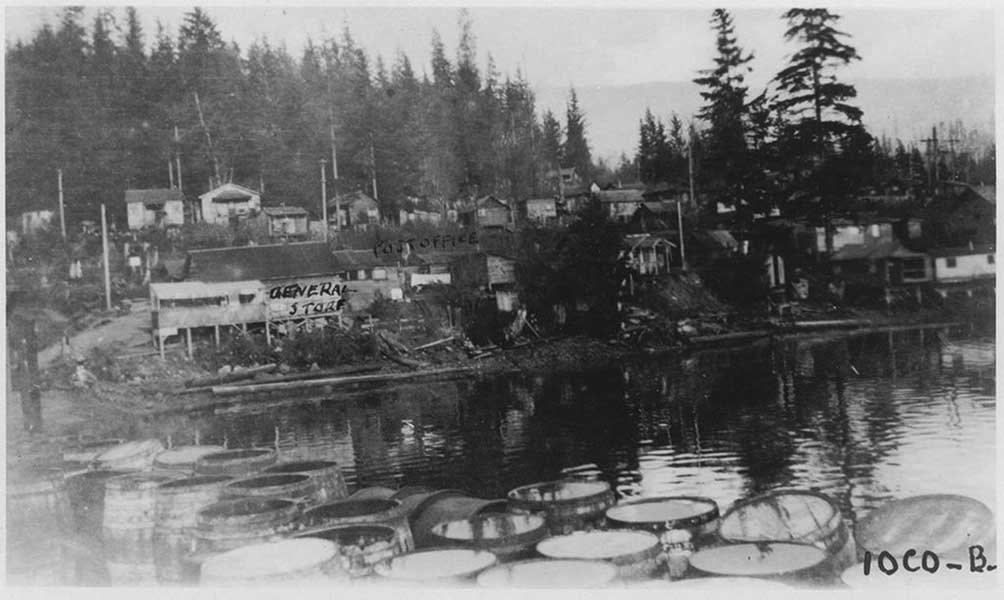

Despite the company’s effort’s, by 1919, 75 percent of workers lived in makeshift dwellings between the shore and the railway tracks. It did not have electricity and oil lamps were a constant source of danger. Water was carried in buckets to homes and residents built communal outhouses.

There was a one room shack where the kids were educated and two general stores. James Crawford was first to build both a house and a store with a post office in 1914. Later, Mr. Briggs erected a store on his scow, known as The Ark. In 1917, one of the first advertisements for the Ioco general store was printed in the Ioco Times. The store was owned by J.B. Gilfillan. Lack of sanitary and heating facilities soon posed health and safety risks. With the population growing and conditions deteriorating, a movement started to establish a proper town.

Community Memories

George Kingsbury

I was born in a little shack inside the Ioco, Imperial Oil Refinery. My dad had a shack right on the water’s edge, in where all the boats came in at the end of the railway. It was sort of a little cove in there, on the other side of the refinery. I was born in there. I was the only child that was ever born inside the refinery. There was a townsite up on the top of the refinery. Way up the hill, they had a townsite of houses and they had a colony house where all the bachelors and the bachelor women, spinster women and the school teacher lived. Dr. Simms came over, by boat. They contacted him somehow and he rowed over by boat from Port Moody and he delivered me in this little shack. He had a midwife there, Mrs. Mogrey with my mother. She used to be midwife for quite a few of the babies that were born in the town. There were other children, I believe, up in the townsite but they weren’t born there. They came when the city, the little town, was made. I was born in ’21 and we lived there until about 1923. The townsite had started down below where it is originally now, with four streets, and they built new homes and then they had dragged the houses from the former townsite that was up in the top of the refinery, they dragged them down and made some of the streets. There were 80 houses in all and some of those old homes are still there on the townsite, and some were new ones built. And of course since then, many of them have been burned down too.

George Kingsbury

We lived in what they called the shacks- right about where Second Avenue is in Ioco. We lived across the road-there was no road at that time, but we lived right across from that. With the creek running alongside us there. Everybody would make their shacks…it wasn’t lumber, they would split these big cedar logs up and make planks out of them.

You had to pack your water from the creek right there by the Ioco School, where the church is now. That’s where everybody used to get their water. Then they’d have to carry it in a bucket. And you’d have outside toilets, there was no flush toilets or anything like that.

Fred Laidlaw

Schooling before Ioco School

“I was in a school down on the beach before while they were building the Ioco School. They had a little room down there that they-The girl-woman-The lady who-Miss [Haley] I think her name was. She used to row in a row boat from Moody over there and teach school and then row back again”.

“In those days you know, they had a big strap in the school. There was a piece of belting that the refinery supplied to her, so you didn’t have to do very much wrong before you got it. The boys. The girls never got slapped. They never got strapped as they called it. But the boys used to. She’d allow you to have about two or three mistakes in spelling and after that you were out there getting your hand out with the strap.

I don’t think the girls ever got it. But she used to line up right at the front and go down there and she had hair with a bun in the back and by the time she would have both feet off the floor when she’d hit you and her bun would be all undone. But she was a marvelous teacher.

Everybody thought the world of her. But I mean she was- We were quite a bunch of roughnecks too you know, It wasn’t any picnic for her and then she’d come and help you at nighttime and then bring you back in her own time and help you with it and strap you the next day for mistakes”.

“An employee after a day’s work should be able to go home and recreate himself for the next day’s work. But we know that anybody living in a shack is never finished work until he is in bed at night. If he buys a half ton of coal or coke, he has got to pack it home sack by sack on his back, oft times a considerable distance along the tracks.”